Central Asia’s endless road

Wild landscapes and rich history make a trip along the Silk Road a real adventure

Words by Ute Junker

Photos supplied

A longer version of this story first appeared in Departures magazine.

It may be the greatest bargain in all of Central Asia. To experience one of the Silk Road’s greatest architectural wonders – the glittering blue-tiled Registan complex in the ancient city of Samarkand – without a single other soul around, all you need is 50,000 Uzbek som, or around US$7.

Well, that and a wake-up call. Don’t make it too early, though. I find myself so excited to be in the fabled city of Samarkand that on my first morning I’m up at five am, arriving at the Registan well before six. The only thing moving in the square is a delivery van driver, carrying an armload of boxes into the interiors of one of the madrassahs. A guard stands near the locked entrance but, when I approach him, he shakes his head and turns away.

It takes me a moment to work out what’s going on: he doesn’t want witnesses. I wait until the delivery truck is gone, just after six am, and repeat my offer. This time he happily takes my money and I spend half an hour admiring the magnificent facades of the mighty madrasahs that line three sides of the Registan’s central square.

I am entranced by the intricate motifs that seem to swirl and dance around each other, intrigued by the lions depicted on one of the madrasahs, and revelling in the fact that I have it all to myself.

You might expect this magical moment to be the highlight of my stay in Samarkand but this city has more surprises in store – not least the fact that, when I return to the Registan during official opening hours, this World Heritage-listed site is nowhere near as crowded as I expected. It is a reminder that, while Central Asia may have endless layers of history and landscapes of a scale that can’t be captured by a camera, one thing it doesn’t have is hordes of tourists.

No wonder, then, that Central Asia feels like the last frontier, a place almost out of reach. In fact, as I discover when I start researching my trip, it’s surprisingly accessible. A flight from Dubai will land you here in around three hours.

Having worked out how to get here, I face a more difficult task: deciding what to do. For some, the lure of Central Asia is adventuring in some of the greatest outdoors around: hiking and riding across vast steppes, climbing and trekking in some of the world’s highest mountain ranges.

Others are intrigued by rapidly-modernising cities such as Ashgabat and Dushanbe, places where eye-catching architecture sits side by side with traditional ways of life.

Me, I’m drawn by the romance of the Silk Road, the ancient trade routes that threaded their way through these lands, connecting China with the west. For centuries upon centuries, countless loads of precious goods – textiles and tea, gems and gold, perfume and even slaves – were passed on relay-style across a series of trading entrepots. Fortunes were made and lost, local khanates rose and fell, foreign conquerors swept in and were later driven out again.

Alexander the Great and his men rampaged through the area, as did Genghis Khan. Timur the Great ruled with a bloody fist over large swathes of territory, and no fewer than three Persian empires also left their legacy. They were succeeded by Arab-led armies that converted the populations to Islam and, centuries later, by Russians: first imperial troops, later the Soviet Red Army.

Keen to dive deep into this little-known history, I choose a tour led by archaeologist Iain Shearer. Formerly a curator at the British Museum, Shearer helms the Splendours of Central Asia tour – presented by Renaissance Tours in partnership with the Art Gallery of NSW Members as part of their World Art Tours program – that takes in the best of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Over our 19-day trip we cross mountain ranges, dip our feet in glacial lakes and wander through fascinating ruins – some thousands of years old, some only recently rediscovered – where the only other visitors are butterflies drifting over the grass.

Much of what we find is unexpected. In Kyrgyzstan, where rivers tumble through verdant valleys, we discover that the impressive horse skills of the nomadic past still flourish today. In Uzbekistan we are charmed by a metro station that celebrates Soviet cosmonauts such as Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova, the first man and woman in space. And in Tajikistan, we are enchanted by the local sheep with their fat bottoms, and even more delighted when a local tells us they are now known as “Kim Kardashian sheep”.

There is the joy of exploring places none of have ever heard of: Karakol and Osh, Fergana and Kokand. The latter is a delight, with a colourful bazaar where traders are intrigued by the foreign visitors, urging us to sample their apricots and peanuts; a mosque with 99 exquisitely-carved wooden columns; and the expansively-conceived Khudayar Khan Palace, designed with 100 rooms set around seven courtyards.

The last ruler of the Kokand khanate, Shearer tells us, built the palace in part to display his own power, in part to convince his mother to give up her embarrassingly old-school ways and finally move out of the yurt that was her preferred lodging.

He had mixed success. His subjects may have been impressed but his mother was not. She set up her yurt in one of the courtyards and continued to sleep in there.

Our most memorable experience in Kokand, however, is lunch. Our local guide leads us into a residential neighbourhood where we enter a simple house with a blue door. What awaits behind that door astonishes us.

Although we have already become accustomed to the gardens that locals tend so lovingly – a legacy of the long Persian rule – this garden is spectacular, with lush fruit trees beneath which sits a long table laden with a fantastic feast.

There are fresh fruits – apricots and cherries so flavourful and aromatic, you can smell them from metres away – fresh salads and round loaves of bread still warm from the oven. Course after course follows, each as delicious as the first. Even better than the food is the wonderfully warm welcome from our hosts, one that is repeated everywhere we visit.

Our itinerary covers a lot of ground and often the journey is as compelling as the destination. One of my absolute highlights turns out to be a day spent largely on the road, travelling from the northern Tajik city of Khujand (known during Soviet times as Leninabad) to the capital of Dushanbe, through Tajikistan’s high mountain passes.

More than 90 per cent of Tajikistan is covered in mountains, half of which are over 3000 metres. The road winds its way past snow-capped peaks and glacial rivers, through high-altitude valleys where wild irises and tulips thrive and where snow leopards still roam. It is some of the most awe-inspiring scenery I have ever seen.

It’s not all slow travel, however. Uzbekistan’s Afrosiyab high-speed rail links key Uzbek cities including Tashkent, Samarkand and Bukhara, allowing us to move at speeds that Genghis Khan’s fleet-footed hordes could only have dreamt of.

The rival cities of Samarkand and Bukhara, built around oases where trade routes intersected, are the Silk Road’s most famous destinations and rightly so. Bukhara was one of the last independent khanates to fall to the Red Army back in 1920. Shearer describes how the last emir fled towards Dushanbe in his Rolls Royce accompanied by as many of his favourite dancing boys that could fit. (His harem was left behind and later put to work in Soviet factories.)

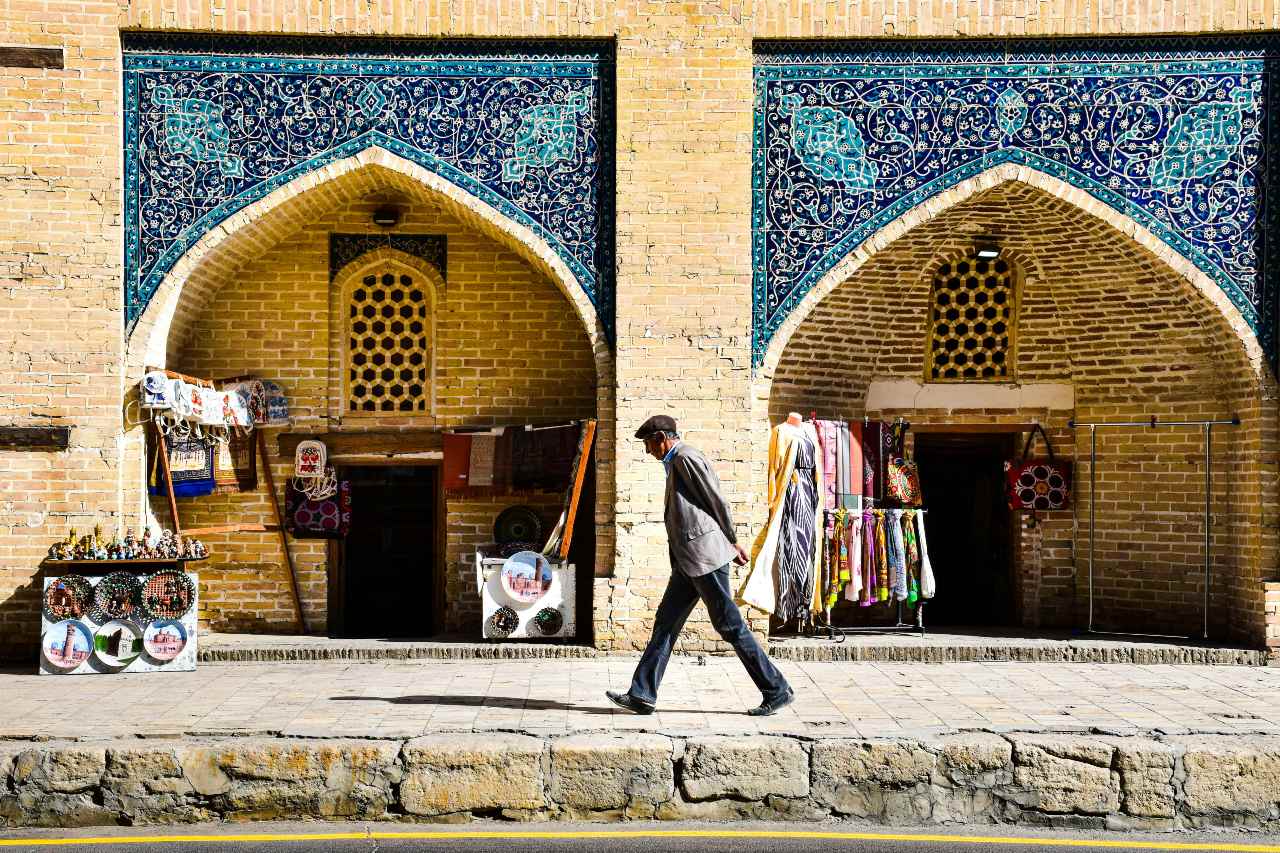

Today Bukhara’s old town is one of the area’s best-preserved Islamic cities, with mosques, minarets and an extraordinary bazaar housed in vaulted arcades where traditional craftsmen show off their wares: piles of silks and carpets, ceramics, miniatures and more.

Bukhara may be beautiful but Samarkand is the city that wins my heart. Much of its beauty was created by Timur the Lame, the warlord known to contemporary Europeans as Tamburlaine, whose love for scholars and opulent architecture was matched only by his bloodthirstiness.

The Registan square is not Samarkand’s only dazzling monument. My personal favourite is the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, a collection of Timurid mausoleums created over eight centuries. Crammed together likes books on a library shelf, the tiled facades in deep shades of ultramarine, turquoise and deep jade positively shimmer with an otherworldly beauty.

You might also like:

Is this Central America’s most underrated destination?